The Paris Cinema Project

One week before filming was set to begin in April 1947, Combat announced the news: “Philosopher, novelist, and playwright Jean-Paul Sartre is now preparing to plant the flag of existentialism in the unknown land of cinema.” For the next six months, Les Jeux sont faits, Sartre’s first film, would be covered extensively by Parisian newspapers, with critics and intellectuals all looking forward to this new effort by the man France-soir referred to as the “Pope of existentialism.” Indeed, because Sartre wrote the screenplay (with some assistance from Jacques-Laurent Bost), the coverage of the film dealt with such serious issues as cinema’s suitability to engage in philosophical debate and the status of the image versus the printed word. But by the time the movie opened in Paris, there was even some discussion—much of it begun by Sartre himself—as to whether or not the film was existentialist at all.

Jean Delannoy would direct Sartre’s screenplay, and he seemed to be the perfect choice for the job. This was a few years before Delannoy would become, for François Truffaut in his famous diatribe Une certaine tendance du cinéma français (A Certain Tendency of the French Cinema), one of the central problems of filmmaking in France, disparaged as a director of “strictly commercial enterprises” and wholly dependent on the talents of his screenwriters. In 1947, the French film press considered him an ideal interpreter of Sartre, having already made one of the most popular—and critically praised—films of 1946, La Symphonie pastorale, as well as L’Éternel retour in 1943, working from a screenplay by Jean Cocteau, one of the very few writers at the time who may have been considered almost as important as Sartre on the French cultural scene.

Delannoy, in fact, took credit for getting the film made at all, telling France-soir in September 1947 that he had gotten “discouraged by the mediocrity of the scripts” that had been submitted to him, and as a result he had gone “to see Sartre to ask if he might want to” write something for him. Nevertheless, it was Sartre, rather than Delannoy, who provided all of the anticipation and excitement surrounding the film. A critic in Carrefour, for instance, told readers in December 1947, just as the film was opening, that “We have been waiting a long time for Monsieur Jean-Paul Sartre to come to the cinema, really since [his 1938 novel] La Nausée,” and then he added, “cinema, we all believe, is deplorably lacking in [characters like] Antoine Requentin,” the hero of that work.

Les Jeux sont faits premiered at the 1947 Cannes film festival, and reporters were there to talk to Sartre about his film. A journalist from France-soir treated Sartre practically as the festival’s next new movie starlet posing on the beach, emphasizing his “disconcertingly white skin,” as well as the way “the intensity of the sun accentuates his blonde hair, the tender blue of his eyes…his sensual mouth,” and then described the white bathrobe that Sartre wore while he greeted writers. But then, Sartre seemed to forget all about getting a suntan and instead turned serious. He spoke of the primacy of the visual in cinema, “which allows us to express the poetry of the everyday through image rather than language,” and then argued against the philosophical importance of Les Jeux sont faits, telling his interviewer that it was “in no way an existentialist film,” but rather a love story.

This would become a constant of Sartre’s and Delannoy’s discussions about the film, as if trying to convince potential viewers that they wouldn’t be attending a philosophy lecture if they came to see the movie. In an interview in Cinévie in November 1947, Delannoy stressed that “neither Sartre nor I wanted to prove anything,” and added, “the film does not demonstrate anything.” Speaking to France-soir, Sartre insisted that he did not, “for a single moment,” try to introduce any existentialism” into his story. A disappointed press tended to agree with the filmmakers.

In Cinévie, France Roche, who soon would begin acting in movies as well as writing them, but now was writing about film, seemed to sum up critical opinion when she claimed, disparagingly, that “there is nothing less Sartrean than Les Jeux sont faits.” Others claimed that the film was simply too conventional. In Les Jeux sont faits, a woman, played by the great star Micheline Presle, is killed by her husband, and, at the same time, a revolutionary, portrayed by the actor Marcello Pagliero, is assassinated by a traitor. They meet in the afterlife and fall in love, and are granted twenty-four hours back on earth, as ghosts, and will be allowed to stay there, as humans, if they commit themselves fully to each other. Instead, they help other people facing hardships, and so they are brought back to the afterlife, having failed in their efforts and presumably doomed never to be together.

Sartre certainly knew something about the genre of films dealing with the dead brought back to life, and he seemed determined to make a different kind of movie, to subvert audience expectations. He told reporters that he wanted to present “ghosts without gags,” and that neither he nor Delannoy wanted them to have “any invisibility or total or partial translucency,” because, for the audience to be moved, they needed the ghostly characters in front of them…having the same density” as any of the viewers. The love story, he said, would have lost all “emotional virtue if Micheline Presle had been transparent.”

Most critics, however, were surprised at the film’s lack of originality. The reviewer in Gavroche called the film “reminiscent of a certain number of English and American films,” and then reeled off two Hollywood products, Le Défunt recalcitrant (Here Comes Mr. Jordan [1941]) and Un nommé Joe (A Guy Named Joe [1943]), and then the great Michael Powell/Emeric Pressburger film, Question de vie ou de mort (A Matter of Life and Death [1946]).

The film historian Georges Sadoul agreed, and in more forceful terms. He complained that “nothing goes out of fashion faster in cinema…than a formal innovation,” which first becomes “a trend, then a cliché.” By this assessment, Les Jeux sont faits was already out of date. Sadoul had seen it all before, where “the living mingle with the dead on the orders of the good lord.” Surely, Sadoul insisted, if Sartre, “the existentialist philosopher, had gone to the cinema before 1939, he couldn’t have failed to see Topper Le Couple Invisible (Topper [1937]),” about a recently deceased couple that returns to torment a very strait-laced friend. Of course, Topper—one of those “gag” ghost films that Sartre had disparaged–with terrific performances by Constance Bennett, Cary Grant, and Roland Young, is now considered one of the great screwball comedies from the era. It’s not clear if that was quite its reputation in the late-1940s, but Sadoul believed it to be more innovative, and better, than Sartre’s film.

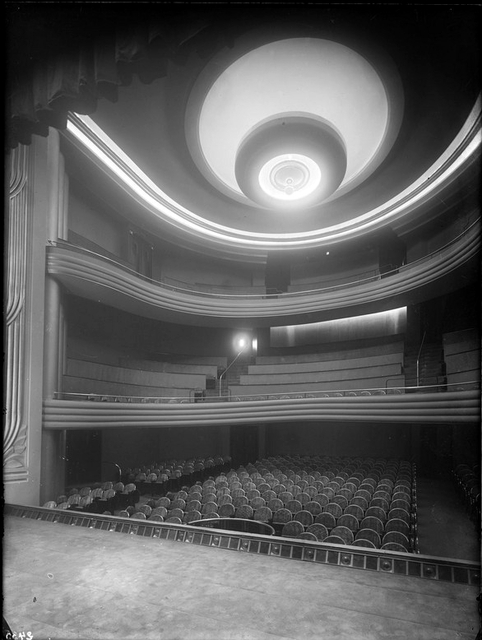

Les Jeux sont faits opened at two of the most important cinémas d’exclusivité in two of the most fashionable neighborhoods in the city, the Marignan in the eighth arrondissement and the Marivaux in the second, in mid-December 1947. Sartre’s film played in those two locations for one month, until the middle of January 1948, perhaps not a great first run, but perfectly respectable nevertheless. When Les Jeux sont faits left, the new film at both locations would be Maurice Tourneur’s latest, Après l’amour (1947), indicating that the cinemas were almost certainly linked at the time as exhibition spaces, with the same movies typically playing in both sites. For the rest of 1948, Les Jeux sont faits fanned out to cinemas in other Parisian neighborhoods.

Les Jeux sont faits was, I believe, Sartre’s only original screenplay to be produced. There would be any number of films based on his plays or novels, and Sartre himself worked on a number of film projects, for instance an adaptation of Arthur Miller’s The Crucible (Les Sorcières de Salem [1957]), and most famously John Huston’s Freud (1962). His film with Delannoy may have been at least something of a disappointment, but it did nothing to diminish Sartre’s reputation. In March 1948, France-soir ran a column, “These are the French most known to foreigners.” Among actors, those chosen were Jean-Lous Barrault and Louis Jouvet, and René Clair was named the director who had the largest following outside of France. There was also Pablo Picasso among painters, a Spaniard claimed as one of France’s own, along with Henri Matisse, with Maurice Chevalier and Charles Trenet the singers with the largest international followings. Sartre was the only artist named in two categories, as both a writer and playwright (sharing the first category with Albert Camus and André Malraux, and the latter with Jean Anouilh and Marcel Pagnol). According to this France-soir poll, Sartre didn’t just share this distinction with Picasso, Pagnol, Camus, and others. He was also just as famous, internationally, as France’s most celebrated export, the most well-known of all perfumes according to the newspaper, Chanel No. 5.

For further relevant reading, see the following post:

Micheline Presle: https://wordpress.com/read/feeds/38257950/posts/5181564594