The Paris Cinema Project

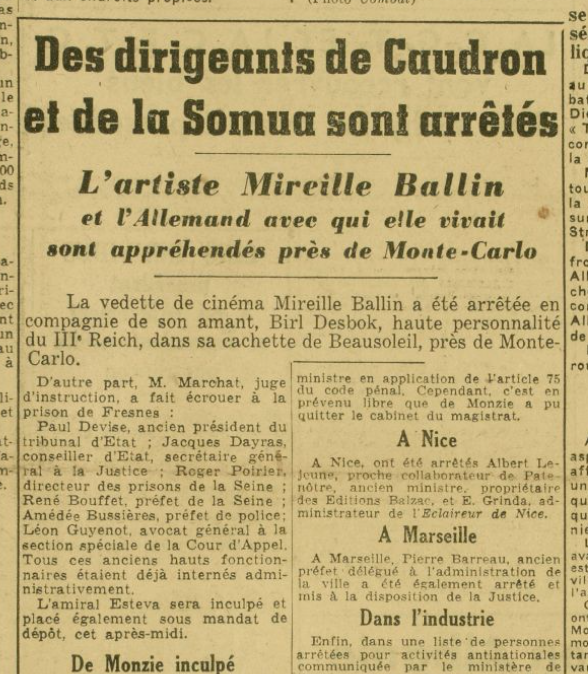

She was the “star gone bad” (une star qui a mal tourné). That’s how Le Jour described Mireille Balin on September 30, 1944, just after she had been captured by French police, a month following the liberation of Paris. Le Jour ran an article that day, “What Has Become of Our Stars” (Que sont devenues nos vedettes), now that the Germans were in full retreat. There were the heroic successes. Marlene Dietrich, for instance, would be returning to France from London, to perform for the allied soldiers. There were also heroic tragedies, as in the case of the great actor Harry Baur. His wife was arrested by the Gestapo as a spy and then Baur himself, trying to save her, had been falsely labelled as Jewish by Nazi authorities, who tortured him. Just after his release, Baur died as a result of his treatment by the Germans. Then there were the actresses who began romantic relationships with Nazis. The comedienne Jocelyn Gaël was the worst of them. She had left her husband, actor Jules Berry, for a notorious Gestapo agent stationed in Lyon. But there was also Balin, captured in a cellar in Beausoleil, in the Riviera, where she was in hiding with “her lover,” the German diplomat Biri Desbok.

Before all that, Balin had been one of the significant stars of French cinema, the “triangle-faced vamp,” as Cinevie described her in 1946, who began making films in 1932. She achieved her greatest success opposite Jean Gabin in Pépé Le Moko (1937), as Gaby, the elegant Parisian who arrives in Algiers, forcing the gangster Pépé to realize everything he has lost during his self-imposed exile in the Casbah. Like many French performers, she continued to work during the German occupation, in such movies as Fromont jeune et Risler aîné (1941) and La femme que j’ai le plus aimée (1942).

Her 1944 arrest was a major news story. All of the reports stressed that authorities found her in a cellar, and emphasized, as L’Echo d’Alger did on October 2, 1944, that she had been there “hiding in the company of a German officer.” They included, as well, the other actresses picked up at around the same time, and for the same reason, for relations with the enemy. As Le Patriote du Sud-Ouest put it, in separate actions the authorities arrested Balin and Gaël, and also Viviane Romance and Gaby Morlay.

Le Patriote expressed the same dismissive scorn towards all of the captured stars, wanting them out of the film industry and hoping that, in twenty years, “in 1964, the community of film actors will be made up of honest women.” Nevertheless, it was a big deal in France when Balin’s new film, La dernière chevauchée, opened in 1947, with the film playing throughout Paris and the rest of the country. Perhaps because Balin finally had been cleared of all charges, the press didn’t condemn her as much as they might have. In December 1944, Ce Soir made the announcement. In an article with news about the latest “purges” (épurations) of collaborationists, which included six executions and two more condemned to death, the newspaper told readers that “Mireille Balin has been freed,” with the judge throwing out the accusations against her.

While reviewers liked Balin’s film, they were more muted about the actress herself, regardless of the judge’s decision. Writing about La dernière chevauchée in La Bourgogne Républicaine in August 1947, the critic Jacquemart lamented that “I can’t help but feel that the celebrations on the third anniversary of the Liberation…were a bit premature, when after walking among all of the joyful Parisians at the Place de l’Hôtel de Ville” in the center of the city, “I saw a movie poster with the face of Mireille Balin.”

Around the same time, a relatively subdued reviewer in La Gazette Provençale announced that most of the performances were excellent, “but we are necessarily more reserved about Mireille Balin.” In the runup to the film, other sources floated the story that she had a gambling problem. France-Soir claimed that she was spotted in Monte Carlo losing 50,000 francs a night, adding “that the rumor continued to circulate around her that there was a German officer…whom she would have married,” and that, in fact, she still wore the engagement ring he had given her. Cinévie also reported that she was gambling away most of her fortune at the roulette wheel, and that these losses prompted Balin to make her return to the screen.

This was nothing, really, compared to the press’ treatment of Jocelyn Gaël. In 1946, Combat reported that she had been found guilty of being an “unworthy” and “hit with a twenty-year exile from Paris.” She was back in the news a year later, when she sued the Free French forces for having stolen millions of francs worth of jewelry from her. In covering that story, Combat reminded readers that she had been condemned as a “national degradation,” and the newspaper groused that the hat she wore at the proceedings was unfashionable. Combat had special contempt for her husband, Jules Berry, who accompanied her in court. He was, after all, the man she had thrown over for a German, and who then had been only too happy to come back to her, “smiling and shrugging casually” during the hearing. The jewels, finally, were returned to Gaël, and Combat complained that the judge in the case had to apologize to the actress, telling her that “we are sorry to have disturbed you unnecessarily.”

The difference in attitude may have been understandable. Newspapers made it clear that Balin’s relationship had been with a German cosmopolitan, Gaël’s with a Gestapo murderer. But Balin’s career never recovered, and La dernière chevauchée, which came out when she was 39, was her final film. She turned up now and then in the news after that, for instance in 1951 when a reporter for V spotted her at the Cannes film festival. He saw her in the company of the Aga Khan as well as the Monarch of Tonkin, Bao Dai, and also with another of the stars arrested in 1944, Viviane Romance. So this, perhaps, marked at least something of a rehabilitation of the reputations of both women.

Really, though, throughout the 1950s and ‘60s she was hardly ever in the news, if we can trust the available sources, which are far fewer than for previous decades. Balin died in 1968, at 59. There were, no doubt, many obituaries, many of them probably extensive. But the only one accessible, at least to the researcher in the United States, is as brief as an obituary can be, even for a faded celebrity. The Journal d’Année for 1968 announced all of the prominent deaths for that year. There was Emmanuel d’Astier de la Vigerie, for instance, “the former editor of Libération,” followed alphabetically by Professeur Jean Baby, “a Marxist theorist.” Then, after Baby, there was Balin, “a film actress, on November 8, 1968, in Paris.”