The Paris Cinema Project

“Le Voleur de bicyclette is, in my eyes, one of the great talking films, and perhaps the highest, most indisputably great thing that cinema has given us since Charlie Chaplin.” That was André Bazin writing about Vittorio de Sica’s 1948 film in Le Parisien liberé, and of course we know that, for him, there could be no higher praise than to compare any movie to a work by the great silent comedian.

Every few years, a film shocked French critics, intellectuals, and artists, showing them possibilities for cinema that they could not have imagined. In 1916, from Paramount Pictures, it was Cecil B. DeMille’s Forfaiture (The Cheat [1915]). In the first year or two of sound, Le Chanteur de jazz (The Jazz Singer [1927]) generated some excitement, but it was Broadway Melody (Broadway Melody of 1928)—a film we remember now for Bessie Love’s spectacular performance, but not much else—that knocked them over. A few years later, from Germany, it would be Josef von Sternberg’s L’Ange Bleu (Der Blaue Engel [1930]. There were also French films that astonished French audiences, for instance Renè Clair’s Sous les toits de Paris (1930) and Jean Renoir’s La Grande illusion (1937). In the years after World War Two, a backlog of incredible movies from the United States and other allied countries, banned during the German occupation, opened seemingly every week in Paris, including, of course, Citizen Kane (1941). There were also new French films that still remain a part of the cinematic canon, for example Marcel Carne’s Les Enfants du paradis (1945). But more than any of them it was an Italian film that stunned all of those in France who took cinema seriously: Le Voleur de bicyclette (Ladri di biciclette, known as Bicycle Thieves in the United States).

De Sica’s film opened in Paris in August 1949, at two of the more important cinémas d’exclusivité in the city, and both in the very fashionable eighth arrondissement: the Biarritz on the Champs-Elysées and the Madeleine on the boulevard de la Madeleine. The locations themselves tell us something about the significance of the film, and, indeed, Le Voleur de bicyclette may have been the most anticipated movie in France of the immediate postwar period.

That interest had been building. Roberto Rossellinni’s Rome ville ouverte (Roma città aperta [1945]), was the first of the neo-realist films to come to Paris in 1947, and had caused something of a sensation, helping establish a French market for Italian films. But along with the excitement generated by De Sica’s new film, there was also the sense that neo-realism had already, perhaps, used itself up.

Writing in Combat when Le Voleur de bicyclette opened, journalist and author (and occasional screenwriter) Jean-Pierre Vivet explained that, “at a time when we believed the vein of what we had called Italian neo-realism to be exhausted…this film is still superior to any previous production,” including Rome ville ouverte, Rossellini’s 1946 film Paisà (1946), and De Sica’s earlier film, Sciuscià (1946, and known in the United States as Shoeshine). This was the sense, really, of so much of the commentary on Le Voleur de bicyclette, that it had surpassed all other neo-realist films. The great film historian Georges Sadoul, in Les Lettres françaises, called it “the culmination, the summit of four years of Italian neo-realism,” and added that “neither Sciuscià, nor Le Soleil se lève encore (Aldo Vergano’s Il Sole sorge encore, from 1946), nor Paisà are this intense and stripped bare.”

So many others felt the same, and described seeing the film in similar terms. In the Communist newspaper L’Humanité, Claude Henares wrote that “it is not easy to define the overwhelming impression left by this film” (l’impression bouleversante), reflected in the “audience’s applause at the end of each screening.” When Jean Cocteau reviewed the film in the rightwing L’Intransigeant, his headline said, simply, “De Sica’s Le Voleur de bicyclette overwhelms us” (Le Voleur de bicyclette…nous bouleverse).

He also called Le Voleur “a masterpiece,” and then Cocteau, whom we associate as a filmmaker with the abstraction and artifice of such movies as Le Sang d’un poète (1930) and La Belle et la Bête (1946), responded most to what he considered the groundbreaking realism of the film, “the theater of the Italian street,” where “the most insignificant woman in the window is an actress, the littlest kid an actor.”

From Bazin to Sadoul to Cocteau, it is hard to find another film from the period that generated such a focused, intense response from so many intellectuals and artists. In fact, Sadoul echoed Bazin, writing that, with this film, De Sica “achieves a universality close to that of Chaplin in Le Gosse (The Kid [1921]), which Le Voleur de bicyclette brings to mind.” The French Communist party leader and journalist Francis Cohen, in L’Humanité in September 1949, held up Le Voleur de bicyclette as the film that fully depicted “the current daily life of workers,” and the model for all “progressive filmmakers.”

Similarly, in 1950, Force Ouvriére, the official newspaper of the Communist party, wrote about a recent “renaissance of the cinema.” The medium was now fifty years old, and for most of that time had served as “the expression of the bourgeoisie.” But there were a few recent films that worked against the commercialism of the cinema and the capitalist class that controlled it. These included Mark Robson’s Le Champion (Champion [1949]), Jacques Tati’s Jour de Fête (1949), Jules Dassin’s La Cité sans voile (Night and the City [1950]), and, more than any of the others, Le Voleur de bicyclette.

Critics other than communists posited Le Voleur against the typical Hollywood films that had such a dominant position in French cinema. David O. Selznick had hoped to produce the film for De Sica, or perhaps make an American version (and would, in fact, work with him in a few years, on Indiscretion of an American Wife/Stazione Termini [1953], which starred Selznick’s wife, Jennifer Jones). In his review, Sadoul breathed a sigh of relief that this hadn’t come to pass, because Selznick would have insisted on casting Cary Grant as the lead actor. An anonymous reviewer for Combat mentioned the same thing, writing that Selznick “wanted Cary Grant to be the main actor,” and then applauded De Sica’s courage and his commitment to a realist model of filmmaking: “De Sica refused, preferring to this professional actor an authentic metallurgical factory worker in Rome, Lamberto Maggiorani.”

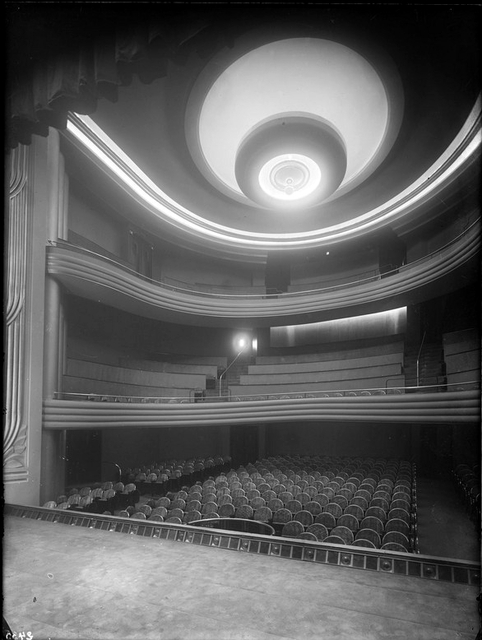

Le Voleur de bicyclette played exclusively at the Biarritz and Madeleine through late-October 1949. Once the film left those locations, it opened again almost without a break at the Ursulines in the fifth arrondissement and at Agriculteurs in the ninth. By early-December, Le Voleur showed at six cinemas throughout Paris. One month later, in January 1950, the film played at fourteen cinemas, including five in the twentieth arrondissement (among them the Palais-Avron, shown in the photo at the heading of this post). If there had been any incongruity in this film, about a desperately poor Italian working class, opening in Paris in the fashionable eighth arrondissement,it was now, at so many cinemas in the twentieth, always one of the poorest neighborhoods, almost certainly screening for audiences who fully understood and related to the predicament of the characters in Le Voleur.

This extended run through the city seemed all the more remarkable because of the film’s apparent failure in Italy. According to Combat, the response to Le Voleur indicated the sophistication of the French audience, because “in Rome, this film only screened for four days.” De Sica’s film, in fact, had a significant and ongoing impact throughout French culture. In January 1950, the tabloid Qui Detective printed something of a joke, headlined “Le Voleur de bicyclette,” about a Parisian traffic cop whose bike was stolen. More seriously, in November 1949, A la page, a weekly for young people, ran a disappointing review of another Italian film, Renato Castellani’s Sous le soleil de Rome (Sotto il sole di Roma [1948]). The critic claimed that he had been eager to see the film only because of the recent reputation of Italian cinema, established primarily by Le Voleur de bicyclette.

We can return to Cocteau for the most deeply felt connection between the film and its audiences, the filmmaker and the French public, and the sensation of seeing Le Voleur de bicyclette in 1949. “I repeat,” Cocteau wrote in L’Intransigeant, “Vitorrio de Sica has arrived at the top of the mountain,” and then he concluded, “like all lovers of new things, we owe him all of our gratitude.”