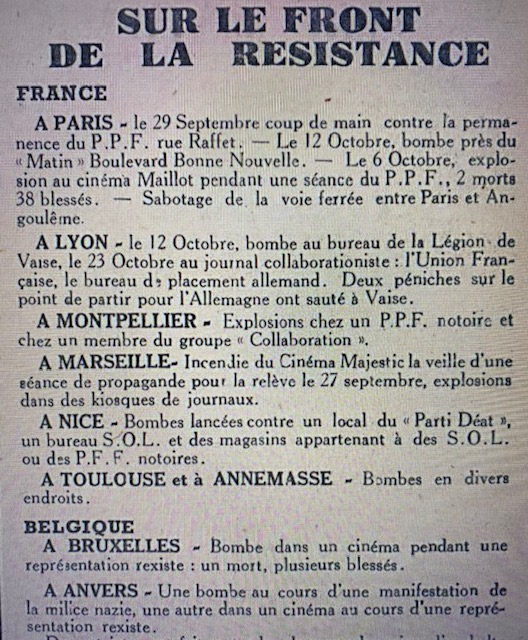

In the edition of November 6, 1942, the French Resistance newspaper Combat reported on victories over the Nazis from the previous month. Mostly, there were bombings, organized by the Resistance against the German military as well as French collaborators. On October 12 in Paris, there was a bombing near the offices of the collaborationist newspaper Le Matin; ten days later, in Lyon, another explosion at another fascist newspaper, L’Union Française. At Montpelier and Nice, Resistance fighters had set off a bomb at the headquarters of the French Fascist Party in the city, and in Toulouse and Annemasse that month, there were too many to count, so Combat simply reported “bombs in various locations.”

There were also attacks on cinemas. In Brussels, for example, a bomb exploded in an unnamed cinema during a screening for the Catholic, far-right Rexist party, with one member of the audience killed and many wounded. In another attack, and the one that particularly interests me here, on October 6 in Paris, the Resistance set off a bomb at the Maillot cinema, on 74 rue de la Grande Armée in the seventeenth arrondissement. The blast killed two and wounded forty-four. I’ve written before about the cinemas in and around Paris as not infrequent sites of fascist violence (see my post at https://wordpress.com/read/blogs/100647815/posts/116). But this incident was a different case altogether, the Maillot as the location of anti-fascist opposition.

The location was a fashionable one, but the 800-seat Maillot was a cinéma de quartier rather than a first-run cinéma d’exclusivité, mostly showing films that had already played elsewhere in the city. Nevertheless, after all 300 or so of the cinemas in Paris had closed by the time of the surrender to Germany, the Maillot was important enough to have been one of the 50 or 60 exhibition sites that the Nazis reopened while they occupied the city. During that first week in October 1942, it had been screening Soyez les bienvenus, an innocuous 1942 comedy starring Gabrielle Dorziat and Jean Mercanton, directed by Jacques de Baroncelli. But on the night of the explosion, the Maillot showed something else, the notoriously anti-Semitic 1940 German film Le Juif Suss (Juf Süß).

Commissioned by the head of Nazi Propaganda Joseph Goebbels and directed by Veit Harlan, the film told the story of the 18th century Jewish banker Joseph Süß Oppenheimer. The movie had already had an extended run in occupied Paris, having opened in February 1941 at the Colisée, a cinéma d’exclusivité on the avenue des Champs Elysées in the eighth arrondissement. After a six-week engagement there, the film went into wide distribution throughout the city. The screening at the Maillot wasn’t part of the film’s movement through Paris, however, but was instead a special, one-night presentation.

Newspapers had been advertising the free screening for several days, so the Resistance certainly had time to make plans. On October 5, for instance, Le Cri du Peuple announced that, at 8:30 the next night, the Maillot would show the “celebrated film Le Juif Suss,” accompanied by a lecture given by Pierre Thurotte, representing the PPF, the French Fascist party. Some newspapers announced, seemingly without irony, that the screening and lecture were part of a conference on anti-Semitism, while others claimed that the evening dealt with le problème juif, “the Jewish problem.” Of course, by this time, the Nazis had solved their Jewish problem, in France and elsewhere. The roundup of Parisian Jews at the Vélodrome d’Hiver in the fifteenth arrondissement—the Vél d’Hiv—and their subsequent deportation to concentration camps had taken place in July 1942, several months before the screening.

The bomb at the Maillot went off about ten minutes into the film. The collaborationist press provided all of the details of the attack, and typically emphasized the innocence of the fascists in attendance. On October 8, Le Cri du Peuple announced that a second victim had died as a result of wounds from the bomb, and then declared that “In placing their bomb in a cinema, the assassins deliberately attacked women, the aged, and children.” Other sources were more measured. Le Journal, for instance, drily informed readers that this second fatality had been a Monsieur Pasteur, sixty years old, a businessman who lived at 18 bis rue de Chartres in Paris, and that his wife had also died in the explosion, with 24 others having been seriously injured while 20 had been slightly hurt.

The Resistance newspaper France reported that the Maillot bombing marked the third attack against the PPF in a week, and that the leader of the party, Jacques Doriot, had confidently announced that he “knew how to exact revenge.” In fact, Doriot and other French fascists might well have expected this attack. In the aftermath of the Maillot explosion, La Croix d’Auvergne wrote that only six weeks before, on August 28, a bomb had been set off in a cinema in the Parisian suburb of Clichy, also during a screening of Le Juif Suss, killing one spectator and injuring 20 others.

Immediately after the Maillot incident, the collaborationist press demanded action, and announced within days of the explosion that an inquest had begun. At least from the available sources, however, nothing seems to have come from this, and the press lost interest after just a few months. None of the reports specifies the precise damage to the Maillot, but within just a few days the cinema was apparently back to business as usual. On October 10, for example, newspaper listings let readers know that they could see René Dary and Paul Azaïs in Léon Mathot’s 1942 film Forte tête there. Even if these listings had been scheduled for publication days before the explosion and were printed even though the location necessarily had to close for repairs, by the end of the month the Maillot was certainly back in operation, with a reissue of Marcel L’Herbier’s Histoire de rire (1942).

The principal characters involved in the incident had varied careers following the explosion. Doriot, the fascist leader who vowed revenge (and who had founded Le Cri du Peuple, which covered the story so fully), died in February 1945 during an air raid by Allied planes. On the other hand, Pierre Thurotte, the lecturer that night at the Maillot, lived until 1984, and seems to have been welcomed back into mainstream French politics after the war, winning election in 1959 as conseiller municipal for Saint-Maur-des-Fossés, just a few miles outside of Paris.

The Maillot remained a cinema in the city until the late 1970’s. The last listing I’ve found comes from the end of July 1977, when two movies played there on alternate days: the 1963 Japanese horror film Atragon on Wednesdays, Fridays, and Sundays, and the 1967 low-budget Italian science fiction film 4,3, 2, 1…Objectif Lune on Thursdays, Saturdays, and Mondays. Before a cinema had been established there in 1916, a restaurant occupied the space at 74 avenue de la Grande Armée, and now once again, today, at this site of anti-fascist resistance in 1942, there is a dining establishment, a Fratellini café, part of a chain of such bistros throughout Paris.

Extremely interesting, Eric, thanks for sharing this piece. Because of the locale, it also reminded me of the now-departed Boite à Films, which was at 47, ave. de la Grande Armée. Fond memories of that one, a small room that closed for the last time in the 80s.

LikeLike

Thanks so much!!! And I’m glad to learn about the Boite, down the block from the Maillot!

LikeLike