“Bravo Nadia! You’ve cleared the hurdle!” That was how the magazine V introduced readers to Nadia Gretchikin, “a beautiful 20-year old brunette,” who just happened to have been elected “Miss Cinéma” for 1950, at a gala ceremony at the Moulin Rouge. Fully convinced of the significance of the event, V called Nadia’s election “The Promotion of the Half-Century” and celebrated the importance of the jury of electors, which included singer-songwriter Roland Toutain, director Henri Calef, the actor Henri Genès, and many other notables connected to the film industry. The magazine itself had begun just six years before, in September 1944, as its title would indicate in the immediate aftermath of the liberation of Paris. It moved fairly quickly from a journal of French and European affairs to a more broad-based periodical that routinely included soft-core photos of nude women and occasionally men. But V seemed to take the election of Miss Cinéma seriously, befitting a contest that had been around for a long time, interrupted only by the inconvenience of World War Two.

The earliest Miss Cinéma I’ve found comes from March 1933, mentioned in La Petite Gironde, a newspaper covering one of France’s 83 departments, this one in the Southwest. That area includes Bordeaux, and the newspaper was pleased to announce that the contest winner had represented that city, while providing no other information about her—-not even her name—-or how she had been chosen.

By 1935, Miss Cinéma had become something of a big deal, to the extent that Parisian newspapers took notice. The contest now was under the auspices of the Club Cinématographique, one of many ciné-clubs in the city, with the arts and culture newspaper Comoedia announcing on February 18th, 1935, that the winner had just been chosen by a jury that included such luminaries as the director Jaques Feyder. Nevertheless, the attitude in Comoedia, which took the arts scene in Paris very seriously, was mostly dismissive, noting that the young women in the competition were “ersatz” stars, “a fake Thelma Todd, a caricature of Simone Simon…a semblance of Myrna Loy.” Comoedia identified all of the contestants by number, with only the winner–number 31, Lilian Gauthier—-given a name.

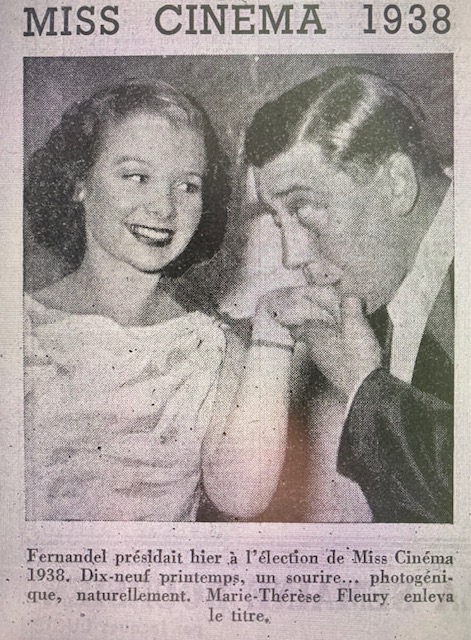

The contest continued for the next few years and seemed to gain in prestige as the Club Cinématograhique partnered with Pour Vous, the most significant French film magazine at the time. In 1937, there was even something of a controversy, when, according to Ce Soir, there were “Two Miss Cinémas in Just One Night,” with an initial vote giving the award to one contestant and then the jurors, after much discussion, deciding on another. Perhaps because of this, a year later, opting for full transparency, Pour Vous published all of the rules governing Miss Cinéma. Contestants needed to prove that they had already appeared in at least one film, they would have to perform a one-minute dramatic scene for the jury, and they needed to be free for all future Miss Cinéma engagements. Ce Soir printed the results, complete with photographs, with the great comic star Fernandel shown crowning the new winner, Marie-Thérèse Fleury.

A few months later, Pour Vous announced that Fleury would appear in a new film directed by Henry Wulschleger, which would become the comedy Gargousse (1938). Fleury played in just one more movie, Raphaël le tatoué, which starred Fernandel, with that film, apparently, marking the end of her acting career. One year later, Pour Vous hosted a “gala dinner” for Miss Cinéma 1939, but just after that, of course, both the journal, which ceased publication, and the annual award were the victims of the war in Europe and the Nazi occupation of France.

It would be fitting, then, that the contest began again in 1946, organized by the film industry based Groupements des Producteurs de Films, as one of the signs that French cinema, as it had been understood and experienced before the war, had returned, liberated from German control. By 1949, V had taken over the contest, a magazine celebrating the liberation celebrating, as well, the return of prewar French film culture.

In April 1949, V ran a series of articles, first alerting readers that they would be voting for the most “photogenic” entrant, who, as the new Miss Cinéma, would be guaranteed a role in the next film by director Marc Allégret, and then providing photos of the fifteen women in the competition. One month later, the magazine announced that readers’ votes would be tallied along with those of an expert jury, and the members give us the best indication that Miss Cinéma had achieved at least some cultural importance. Allégret himself would be a judge, along with perhaps the two greatest of all French stars at the time, Michèle Morgan and Danielle Darrieux, referred to by V as the Grandes electrices de Miss Cinéma ’49. All of these experts decided on Monique Chanière, in what V characterized as a landslide, an écrasante majorité. Despite the victory, however, and the promised prize to the winner, Chanière seems to have appeared in no movies, by Allégret or anyone else.

Morgan, Darrieux, and Allégret apparently marked the high point of the contest. V sponsored Miss Cinéma once again in 1950, and duly celebrated the election of Nadia Gretchikin. But the jurors, despite Toutan, Calef, and some of the others, couldn’t match the star power of the previous year. V itself would publish for five more years, and while Miss Cinéma may have continued, I have been unable to find any post-1950 mention of the contest in any other periodical, and so perhaps Monique Chanière would be the last one to claim the title.

We celebrate 1950s French film culture, of course, a little too simplistically, as the time of Cahiers du Cinéma and the Nouvelle Vague, a decade that marked important changes in the ways artists and intellectuals wrote and talked about films, and shifts in the ways films looked. Given this, even if we acknowledge that the postwar cinema in France cannot just be reduced to André Bazin, Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, and a few others, it’s easy to imagine that the contest to find the next Miss Cinéma, reinstated after the war to demonstrate that French cinema was, once again, truly French, was already out of step, a relic from an era now long gone.