Parisian authorities could trace Suzanne Barbala’s whereabout on September 1, 1922, with almost absolute precision. The eleven-year-old girl left her home at 4, boulevard Port Royal in the fifth arrondissement in the early afternoon. She walked south to a pharmacy in the nearby thirteenth arrondissement, and then she hoped to visit her grandmother, who also lived in the thirteenth. But her grandmother wasn’t home, and now Suzanne’s motives and intentions became a little less clear. She made her way to the Madelon cinema, at 174 avenue d’Italie in the thirteenth, but probably not to go to the movies. It was raining that day, and so Suzanne may have tried to shelter herself under the marquee, at least until the downpour stopped. After that, the trail seemed to end, and no one would see Suzanne for almost an entire month.

On September 29, 1922, the newspaper L’Oeuvre described the Madelon as a “modest cinema,” with a manager, a pianist, a violinist, and a projectionist who doubled as a janitor. Paris had around 200 cinemas at the time, and the Madelon would be one of the many cinémas des quartiers in the city, a neighborhood cinema that showed films in their subsequent runs. Its programs would never be reported in the city’s newspapers, which tended to concentrate on the far more important cinémas d’exclusivité, the first-run exhibition sites, and so it is impossible to tell now, one hundred years later, what was showing on the day of Suzanne’s disappearance. The best evidence we have for the Madelon comes from a November 1922 edition of L’Economiste Français that listed the 1921 “gross receipts” for all of the city’s cinemas. The Madelon reported only 108,000 francs for that year, not the lowest in the city, but far away from the 1.7 million earned by the Neauveautés, the 1.5 million taken in by the Omnia, or the revenues from many other larger, more important cinemas.

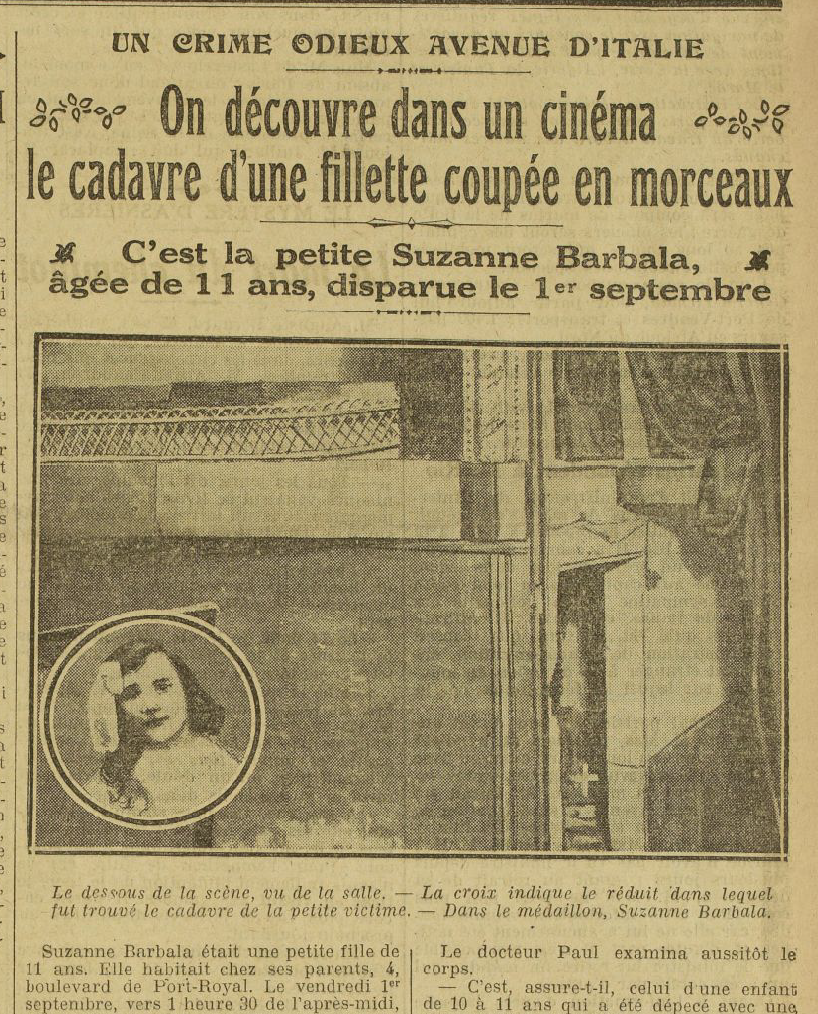

It was at the end of September 1922 that the pianist at the Madelon, accompanying a silent film, complained about a terrible smell coming from around the screen. As reported in most of the city’s newspapers, this led to a search of the space in back of the screen, and to a grim discovery; a body. At first, the Madelon staff thought it must be that of an animal, but then as L’Oeuvre wrote, “they saw it was human,” and that, grimly, it had been expertly “cut into pieces.”

A doctor identified the body as that of a young girl, and then it was determined to be Suzanne, who had been missing for weeks. The autopsy showed that she had put up a significant fight, but that the murderer had overpowered her. Authorities believed that she had been killed near the cinema, perhaps as she sought shelter there from the rain, and then her body hidden behind the screen.

Each day, new details came out. In early-October, Le Journal reported that the murderer must have been a regular at the cinema, and he must have known Suzanne well. Each of the cinema’s employees was questioned, and each one ruled out, except for one, the manager, Jean Cuvillier. Le Journal went on that it was he who reported the murder, but that he had been suspiciously “drenched in sweat” as he spoke to police. He seemed to physically fit the part of murderer. He was about “fifty years old, very strong…with big hands, a big mustache, and a heavy air.” As an afterthought, the story provided something of his employment history, which would later become significant. Before the war, he had managed a cinema in Reims, about 75 miles outside of Paris.

Cuvillier maintained his innocence and named two other suspects, as L’Action Française explained on October 7, the projectionist and a young man who did odd jobs around the Madelon. Meanwhile, the press suggested other possible murderers, for example a man who sold flowers on the avenue d’Italie, named by L’Avenir in November 1922.

Nevertheless, most of the attention remained on Cuvillier. As hard as they tried, authorities couldn’t prove he was involved in Suzanne’s murder. But they did find troubling details from his past, in Reims. As it turned out, he had been charged there with assaulting a young girl, but the beginning of the war had interrupted his trial, and he had conveniently left for Paris. After police arrested him as a suspect in the Madelon murder, that earlier charge was reinstated, and in March newspapers reported that he had been sentenced to four years in prison for his guilt in the earlier case.

That still left Suzanne’s murder unsolved, even though suspicion reasonably remained on Cuvillier. In fact, Parisian police never found the person responsible. The press reported on the case frequently, at least until Cuvillier’s sentencing for the previous crime. After that, the case came up now an again, for instance in December 1924, when Le Matin ran an article about “Perpetrators Who Have Escaped Justice for Their Crimes,” about Suzanne’s murder and also that of another very young girl, as well as a few others killed under mysterious circumstances. Two years later, in 1926, Le Petit Journal informed readers that the skeleton of a young girl had been found just outside Paris,in Rambouillet, and began its coverage with, “A new crime, one that brings to mind the murder at the Madelon cinema of the young Suzanne Barbala…has been discovered.” As late as 1929, the case remained a touchstone for legal caution as well as for unintended results. That’s when L’Oeuvre ran an article, “Respect for the Condemned and Contempt for Witnesses,” reminding readers that Cuvillier had been all but convicted although apparently through false testimony, and then had been justifiably—and almost accidentally—found guilty of serious previous crimes.

As a sign of the ongoing impact of the case on French culture, in 1928 L’Avenir ran a brief piece about various murderers, dating back to the mid-nineteenth century. The article highlighted the most famous and frightening of all the country’s serial killers, Henri Landru, who murdered at least eleven people, all but one of them women, and possibly dozens more during the war, before he was arrested, found guilty, and executed in 1922. The newspaper likened his victims to “the petite Suzanne Barbala,” whose “horribly mutilated body was hidden at the Madelon cinema,” and his methods to Suzanne’s murderer. With this comparison to the terrifying, remorseless Landru, Barbala’s unidentified murderer clearly had entered a pantheon of French criminals.

Perhaps because of the Madelon’s ongoing association with Suzanne’s death, the cinema had changed its name by 1928, the same year as the reference in L’Avenir to Landru and the first year for which I can find reliable listings. By then, the cinema would be identified by its location, on the avenue d’Italie, as the Ciné-Italie. The Italie continued as an exhibition site at least until the beginning of World War Two, when, like all other cinemas in the city, it closed with the German occupation of the city. Over the course of the occupation, the Germans reopened about fifty cinemas, but the small, neighborhood Italie was not one of them. It may have become a working cinema again after the liberation, but by 1949 and the first postwar listings for the entire city that I have been able to locate, there is no longer any cinema at 174, avenue d’Italie. Now, in 2023, there is a housing development at the site, in a style from the 1960s or 70s, with no sign at all of the Madelon cinema, and certainly no indication of the crime that had been discovered there more than one hundred years ago, and that was never solved.

Quite a story!

LikeLike