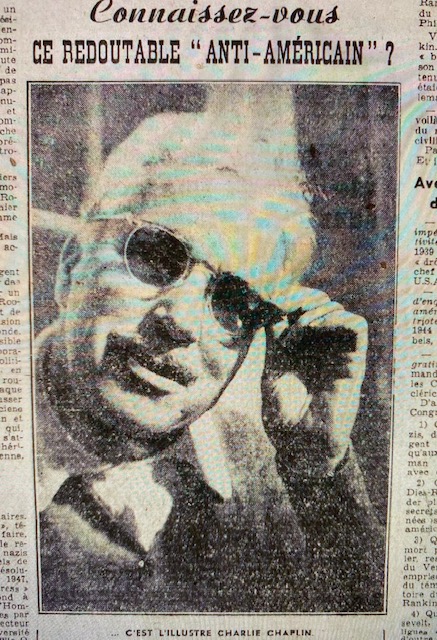

The French press was incredulous. How could apparently responsible government officials in the United States imagine that Charlie Chaplin might be a communist? On December 14, 1946, L’Aurore ran the headline, “Charlie Chaplin Accused of Un-American Activities,” and in the article itself referred to the great star, endearingly, with the name French viewers had given him years before, Charlot. A few months later, in May 1947, the leftwing newspaper Ce Soir ran a story about the anti-communist hysteria in the United States and accompanied it with a picture of an aged, smiling Chaplin, and the ironic caption, “Do you know this formidable ‘anti-American’?” Even the rightwing L’Intransigeant questioned the accusations against the actor, letting him speak for himself in an article from June, 1947: “Chaplin told Hollywood, ‘This kind of procedure is the usual technique employed by fascists to suppress freedom of speech and freedom of expression in cinema.’” Thus began the coverage of the Hollywood blacklist in French newspapers. For the next five years or so, and across the ideological spectrum, those sources, or at least those readily available to the contemporary researcher, forcefully criticized efforts to rid Hollywood of leftists, not just Chaplin but many others. They also endlessly ridiculed those “friendly” witnesses—Adolphe Menjou and Robert Taylor, for instance—who had sounded the alarm over the radicalization of the American film industry.

For the first few years, Chaplin remained the touchstone for critics. In October, 1947, for example, in the journal of cultural affairs Les Lettres Françaises, Soviet historian Ilya Ehrenbourg linked American anti-communism with American racism, claiming that it was House Un-American Activities Committee [HUAC] member John Rankin, from Mississippi, a state “full of slaves and slave owners,” who demanded Chaplin’s expulsion from the United States as well as the investigation of others, like Dorothy Parker. To Eherenburg, these investigations were prompted simply because these suspected communists “value culture, they love art, and…they hate the dollar and the whip, both of which Rankin represents.” But the press also took note of the specious accusations against other performers besides Chaplin, major stars and celebrities who were known for leftwing politics, for instance Frank Sinatra and Orson Welles. Sometimes, though, French journalists couldn’t help but point out the strangeness of the Red Scare, and also its silliness.

In “Civil War Among Movie Stars,” Bernard Valéry, reporting from Hollywood in August, 1947 for France-Soir and with his tongue very much in his cheek, wrote that the debate about communists was the only thing he heard about as he lounged by his hotel pool, or took in the scene at the nightclub Mocambo. He complained about Menjou and Taylor, as well as all the others—Gary Cooper, Clark Gable, and Spencer Tracy—willing to turn against their colleagues. Underscoring what he found to be the humor in all of this, he claimed that he still could not confirm whether former child star Shirley Temple would testify before HUAC.

In 1947, Valéry may have seen the comedy in the Red Scare. But most of the French press took it quite seriously. We might think of the Hollywood blacklist primarily as a domestic issue, perhaps without much of an impact outside of the United States. But interest in, and concern about, la liste noire, as it was called in the French press, seems to have been as global as most Hollywood movies, or any other gossip about Hollywood stars that would turn up in fan magazines around the world.

The communist newspaper L’Humanité made its position clear when it condemned “the fascist Gary Cooper and the snitch Adolphe Menjou,” but even the less ideologically charged newspapers understood the stakes of the American inquest, and knew which side to take. La Gazette, for instance, in November 1947, alerted readers that there was a resistance, made up of Eddie Cantor, Ava Gardner, John Garfield, and still more stars, while Humphrey Bogart, Rita Hayworth, Katharine Hepburn, Myrna Loy, and others had formed a committee to counteract HUAC. The reporter then condemned not only Cooper, Menjou, and Taylor, but also Ginger Rogers, Barbara Stanwyck, and Walt Disney for their “friendly” testimony.

Always, however, special scorn was reserved for the two men the press considered the real villains: Rankin and J. Parnell Thomas, the chair of HUAC. L’Humanité was delighted to report in October 1948 that the latter “was a con artist” who had just been charged with fraud and would be appearing before a grand jury. Two years later, Ce Soir noted that Thomas now served time in jail, but also let readers know that he would be released before any of the Hollywood Ten whom he had sent to prison.

Chaplin’s extraordinary popularity in France is well-known to us today, and so it makes sense that the press there singled out his case to highlight the idiocy of the blacklist. But there was also another filmmaker, and in particular one of his films, that galvanized much of French journalism against American rightwing extremism. Edward Dmytryk’s 1947 critique of anti-semitism, Crossfire, had been a very big hit in Paris as well as the rest of France (a country with its own extended history of anti-semitism). Film scholars now think of Dmytryk as one of the villains of the blacklist, one of the men who named names in order to have his own prison sentence reduced, probably second only to Elia Kazan in terms of the scorn history has heaped upon him. But in the late-1940s, before he turned into a “friendly” witness and at least in Parisian newspapers, Dmytryk was a hero of free speech and progressive politics.

In October 1947, Combat headlined, “Crossfire Filmmakers Sued for Contempt of Congress,” and then explained how Dmytryk as well as Adrian Scott, the producer of the film, had been charged by HUAC. A month later, the Jewish newspaper Droite et Liberté, writing about the director’s blacklisting, explained that “there was a director in Hollywood, Edward Dmytryk, who made a film against anti-semitism.” Directly linking Dmytryk’s prison sentence to the HUAC members’ general attitude towards Jews, the newspaper continued that, as a result of that film, “HUAC took him to court and expelled him from Hollywood.” To emphasize the point, Droite et Liberté concluded, “So much for democracy.”

Over the course of covering the Red Scare in Hollywood, the press would return to Chaplin. In April, 1949, Ce Soir celebrated the actor’s sixtieth birthday, and in assessing his life up to then wrote that Chaplin had five children “and millions of friends around the world.” And yet, Ce Soir lamented, after thirty years of “good and loyal service,” Hollywood wanted to throw him out. Instead, the newspaper suggested that he receive the Nobel Peace Prize.

Along with remembering Chaplin, many French journalists refused to forget those who had named names and accused their friends and colleagues of being traitors. In October, 1950, Ce Soir ran the story, “Robert Taylor Films Conspirator.” This sounds like so many other articles in French newspapers, publicity pieces about actors and the films they were making. But this one reads differently from the beginning. “In Washington, I saw Robert Taylor play his natural role as snitch and informer,” the reporter, Francis Crémieux, wrote, and then added, “That was in 1947, in front of HUAC,” with the detail that Taylor had been “accompanied by his little parrot, Adolphe Menjou.” Crémieux related his experience of those events, telling readers, “I’ll never forget Taylor’s face, the well-combed seducer, a face like Don Juan…That was one of the most repulsive spectacles that I’ve ever seen…Taylor, an auxiliary of the FBI, with his bosses’ blessing.”

According to Crémieux, Taylor’s reward from those “bosses,” the studio heads, was his casting in Conspirator, director Victor Saville’s 1949 anti-communist propaganda film that co-starred Elizabeth Taylor. By this time, the press no longer joked about child star Shirley Temple as a possible anti-American. Instead, they ran headlines like another one from Ce Soir, from June, 1950: “Banished From the Studios Because of a Blacklist: The 10 Best Screenwriters in Hollywood Will Each Spend a Year in Prison.” The article expressed no hope, because “the Supreme Court had confirmed” the sentences of the ten, “whose films are among the greatest successes in American cinema.” The problem extended beyond those few screenwriters, however, with the article including the “hundreds of other artists and technicians” who had been named before HUAC. In France, which had its own history of irrational anti-communism, particularly in the postwar period, the press broadly understood la liste noire as a catastrophe, for the great Chaplin as well as for the anonymous artisans who might never have been credited in the movies they helped make, and who might never have the chance to work again.